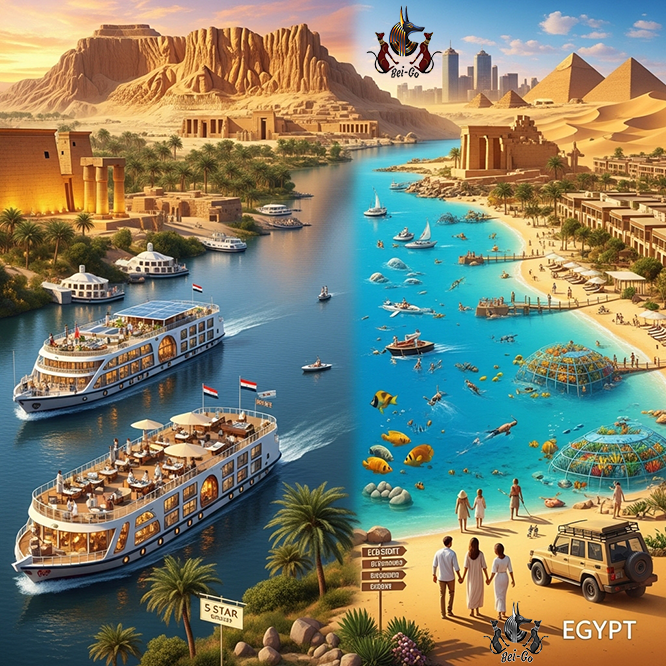

Geography of Ancient Egypt: The Key to an Eternal Civilization on the Banks of the Nile

The Nile: Artery of Life and Regulator of Existence

The Nile River was the definitive geographical force that shaped the development and longevity of Ancient Egyptian civilization. Flowing over 6,600 kilometers from south to north, it created a stark division between the narrow, fertile river valley of Upper Egypt and the broad, marshy Delta of Lower Egypt. Far more than a simple water source, the Nile was the primary regulator of existence through its predictable annual flooding cycle. This cycle consisted of three distinct seasons: Akhet (inundation), Peret (growth), and Shemu (harvest). These floods deposited millions of tons of nutrient-rich, black silt across the floodplain, transforming an otherwise arid landscape into the most productive agricultural zone in the ancient world. This natural fertilization generated a massive food surplus, which served as the economic foundation of the state. Without this surplus, the population could not have diverted labor toward monumental construction projects, the development of advanced mathematics, or the administration of a complex empire. Furthermore, the Nile served as the nation's essential transport and communication corridor. Prevailing winds blowing south allowed boats to sail upstream, while the current carried them north, seamlessly connecting distant nomes (provinces) and facilitating a centralized government under the Pharaoh.

The Red Land and the Black Land: Natural Fortification

The deserts surrounding the Nile Valley were crucial geographical elements, providing both protection and vital resources. The ancient Egyptians characterized their world by color: Kemet (the Black Land) was the thin strip of fertile soil along the river, while Deshret (the Red Land) comprised the vast, scorching deserts. The Libyan Desert to the west and the Eastern Desert to the east formed immense natural barriers that isolated the civilization from foreign invasions for millennia. This unique isolation granted Egypt long periods of internal stability, allowing its culture, religion, and language to develop with minimal external disruption compared to the volatile states of Mesopotamia. However, these deserts were not merely empty voids; they were essential treasure houses. They contained the vast quantities of limestone, sandstone, and granite required to build the pyramids and temples that defined the Egyptian identity. Furthermore, the deserts were rich in semi-precious stones and minerals like copper and gold. Scattered oases in the Western Desert, such as Siwa and Bahariya, served as crucial waypoints for trade routes and military outposts, demonstrating the Egyptians' sophisticated ability to master and utilize their harsh, arid environment.

The Nile Delta: A Strategic Gateway and Economic Powerhouse

The Nile Delta, where the river fans out into multiple branches before reaching the Mediterranean Sea, represented a critical geographical junction. Known as Lower Egypt, this low-lying, triangular region was culturally and environmentally distinct from the narrow valley of the south. In antiquity, the Nile split into at least seven branches, with the Rosetta and Damietta branches remaining the most prominent today. This marshy, flat topography provided incredibly rich agricultural land, ideal for cultivating specialized crops like flax for linen and papyrus for writing material. Beyond agriculture, the Delta served as Egypt's primary gateway to the wider world. Proximity to the Mediterranean coast enabled maritime trade and cultural exchange with the Minoans, Mycenaeans, and Phoenicians. This brought new technologies, wealth, and ideas into the kingdom, making the Delta a strategically vital region. While the deserts offered isolation, the Delta provided controlled connectivity, allowing the Pharaohs to maintain a naval presence and manage international relations. The region's complexity required advanced hydraulic engineering to manage the water flow, further driving the Egyptian mastery of surveying and geometry that would later influence the entire Mediterranean basin.

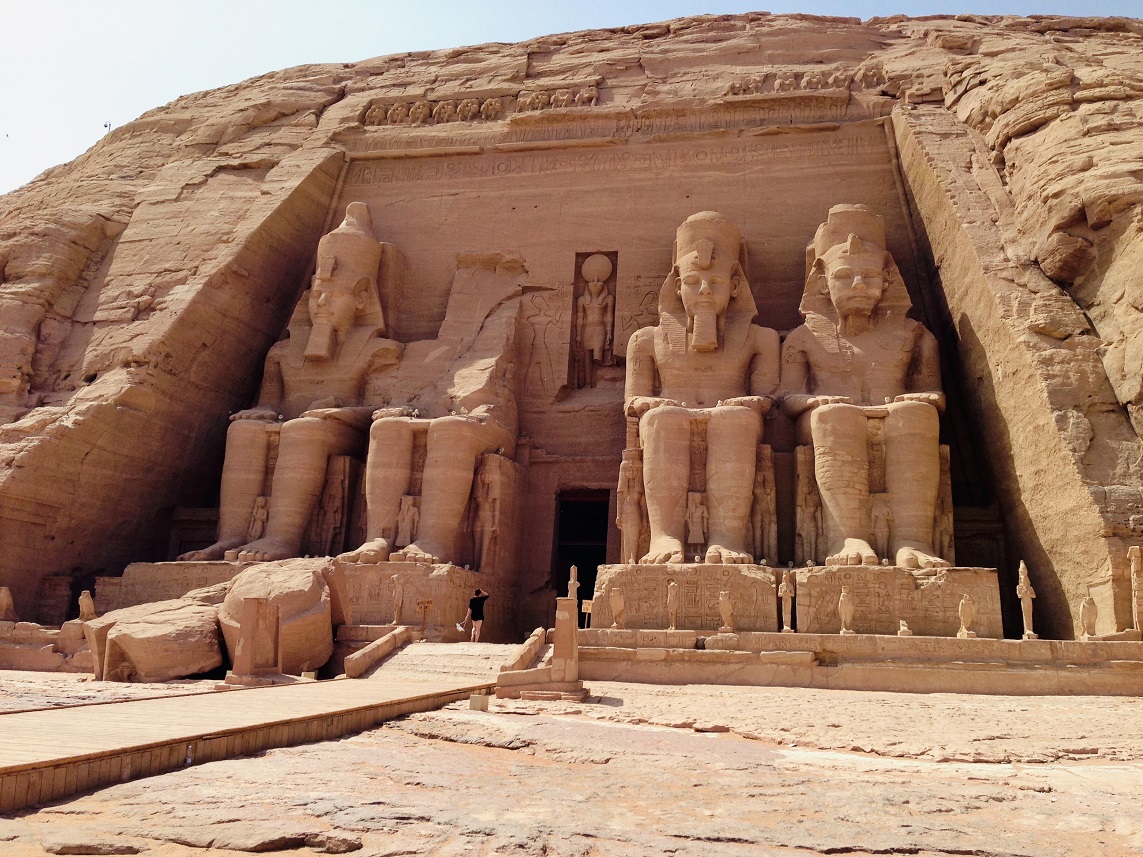

Geological Resources: The Foundation of Architectural Eternity

The grandeur of ancient Egyptian architecture was made possible by the diverse geological resources found within its sun-scorched deserts. The Egyptians viewed stone not just as a building material, but as a medium for eternity. Massive quarries were established across the land to extract specific materials for specific purposes. Quarries at Aswan provided the iconic red granite used for monolithic obelisks and colossal royal statues. Near Cairo, the Tura quarries yielded the fine white limestone that originally cased the Great Pyramids, giving them a brilliant, reflective surface. The Eastern Desert and the Sinai Peninsula were particularly prized for their mineral wealth, producing copper for tools and gold, which the Egyptians considered the "flesh of the gods." Another vital resource was Natron, a naturally occurring salt harvested from the Wadi Natrun. This substance was the essential chemical agent in the mummification process, allowing the Egyptians to preserve the physical body for the afterlife. The Nile served as the logistical backbone for this industry; during the high-water season of Akhet, massive stone blocks were floated on specialized barges from southern quarries to construction sites in the north, showing a level of logistical planning that remains a marvel of human history.

Strategic Borders: Geography as a Military Doctrine

The borders of Ancient Egypt were far more than simple political lines; they were formidable geographical barriers that provided a natural "defense-in-depth" strategy. This environmental fortification allowed the state to flourish for millennia, often prioritizing resources for monumental construction over the maintenance of massive standing armies. To the south, the First Cataract at Aswan—a treacherous stretch of impassable boulders and rapids—served as a natural bottleneck, effectively blocking large-scale naval invasions from the Kingdom of Kush. To the east, the arid Sinai Peninsula acted as a harsh land bridge to Asia, forcing any approaching army through predictable mountain passes and coastal routes that were easily monitored by Egyptian garrisons. Specialists at Bei-Go highlight how this unique geographical configuration created a "protected laboratory" where Egyptian culture could refine its identity in relative isolation. By reinforcing these natural boundaries with strategic fortresses like the "Way of Horus," the Pharaohs transformed the harsh landscape into a deliberate military shield that maintained the kingdom’s sovereignty against external threats for centuries.

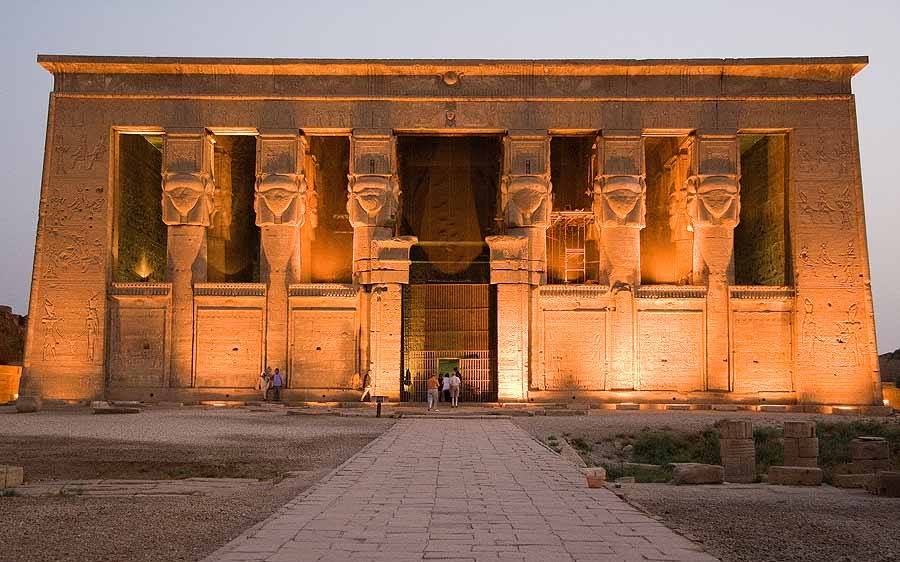

Climatic Diversity: Shaping Regional Culture and Preservation

The pronounced climatic diversity between the northern and southern regions of Egypt fundamentally shaped regional lifestyles and the modern archaeological record. There is a stark contrast between the Mediterranean-influenced climate of the Delta and the hyper-arid environment of Upper Egypt. In the cooler, more humid north, agriculture was exceptionally productive, yet the damp soil was often detrimental to the preservation of organic materials and mudbrick architecture. Conversely, the intense, dry heat of the south, particularly around ancient Thebes, acted as a miraculous natural preservative. This aridity is precisely why we possess the stunningly intact treasures of the Valley of the Kings, including delicate textiles and vibrant wall paintings that have survived for thousands of years. When planning your historical exploration with Bei-Go, you can observe how this climate dictated ancient urban planning: southern homes and temples utilized massive stone walls to mitigate the extreme temperature swings between day and night. This environmental split forced the Egyptians to become masters of adaptation, contributing to the incredible long-term resilience of their civilization.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Egypt's Geography in 2026

Understanding the indissoluble link between the land and the civilization transforms a visit to Egypt into a deep exploration of human ingenuity and environmental mastery. In 2026, this geographical legacy is more accessible than ever, specifically highlighted by the full operation of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) situated at the edge of the Giza plateau. The museum’s very location is a modern tribute to the geography of the past, positioned precisely where the fertile "Green Land" meets the eternal "Red Land." For modern travelers seeking to bridge the gap between history and the physical landscape, Bei-Go provides expertly structured itineraries that contextualize these timeless geographical principles. Whether you are navigating the lush, fan-shaped Delta or standing before the sun-baked granite cliffs of Aswan, you are tracing the contours of a map that has been three thousand years in the making. Geography was never just a background for the Pharaohs; it was the primary architect of their eternity and remains the essential lens through which we view their majesty today.